Tiny Workers, Big Systems: Beekeeping Lessons from the Nilgiris

FarmSay’s notes on early days with bees in Vazhaithottam

Vazhaithottam, a small village on the edge of the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve, set the stage for our beekeeping training. We found ourselves in awe of two things at once: the self-organizing genius of the bees, and the mountain landscape that holds them.

Bees fit into FarmSay’s arc as quiet infrastructure for the food system we care about. Beekeeping forces a wider view: how flowers, trees, seasons, and tiny pollinators all combine to decide whether a harvest succeeds. Learning to keep bees now is a way of committing to that systems view early, while the venture itself is still taking shape.

Obvious fact out of the way: bees are of utmost importance to this planet.

We were fortunate to have exclusive access to trainer Justinraj T. from Keystone Foundation. With over 32 years of experience in this field, we could not have asked for more. To top it, he was very patient with absolute beginners; he neither overwhelmed us with jargon nor left any query unanswered.

Midway through the training, we even witnessed a bee colony rescue and resettlement. This was not part of the curriculum, but the expert eyes of the co-trainer, even during his lunch break, spotted this colony and moved into action.

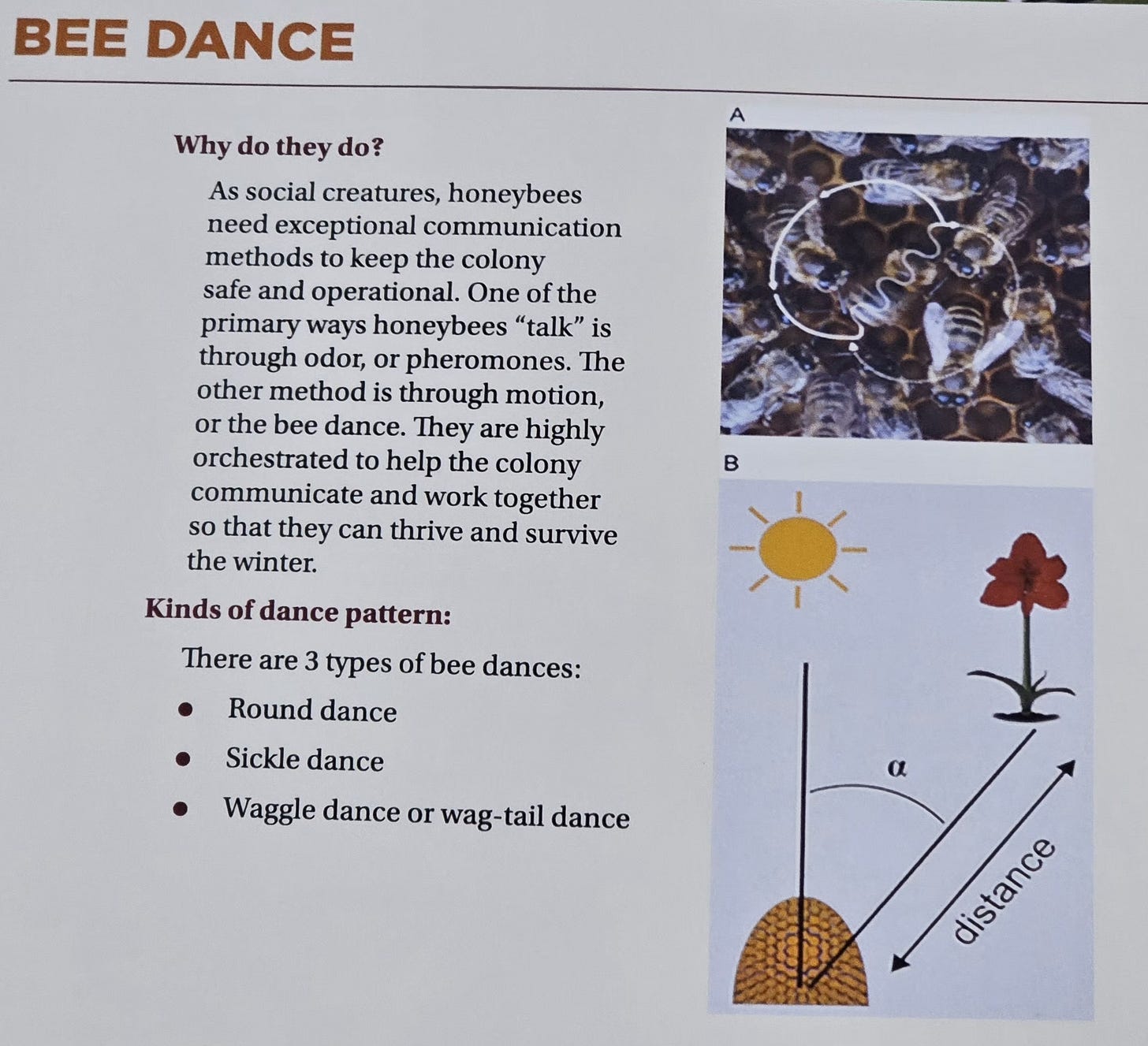

Without diving too much into the training content, the bee “dance language” alone is a solid topic to rabbit-hole into. It is equal parts choreography, navigation system, and information-sharing protocol.

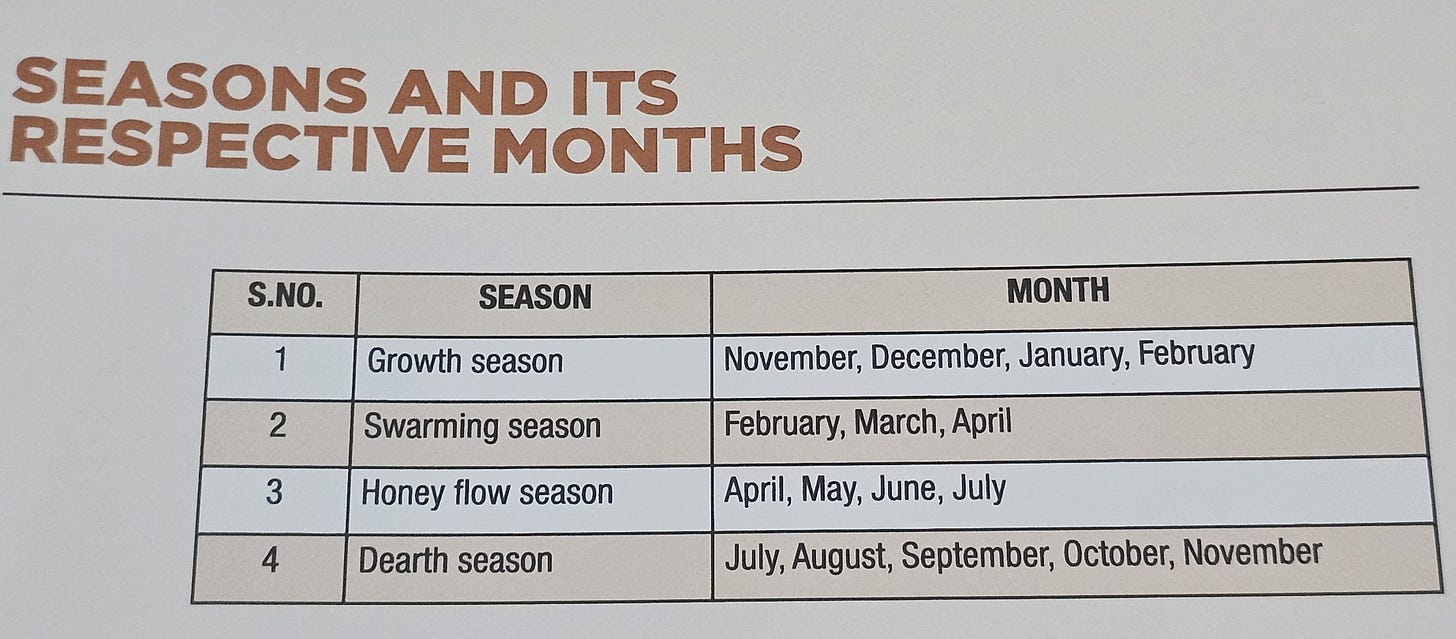

A key moment of truth for us was realizing that we are in the right season for hive growth. That shifts beekeeping from an abstract “someday” into a very real “start now and manage well.”

A few management aspects that stood out:

Beekeeping is not a major financial strain in terms of initial investment and equipment requirements.

Daily effort is low; most of it is simple monitoring for issues such as ants, wasps, or other disturbances.

Market demand is on a steady growth path, especially for more artisanal and traceable varieties of honey.

There is government support through the National Bee Board and state-level efforts such as the Jhenkara brand in Karnataka.

For coconut farmers, managing a few bee boxes can significantly enhance yields through better pollination.

A few watchouts we are carrying back with us:

Placement matters. Sunlight is crucial, but hives must also be shielded from direct heat and rain; there is no need for artificial light.

Bees are prone to a few pests, so a regular, calm eye on the hive goes a long way.

Bees will quietly go about their work 24/7, but human mischief can still disrupt them; intentional disturbance can lead to the odd stray sting, so neighbor engagement and expectations need managing.

In farms, neighboring fields’ pesticide use can harm colonies, especially because bees can forage up to 1–1.5 km from their hive.

Queen bee presence is non-negotiable. A hive is at its best when she is healthy and active, and there is a clear protocol to follow in case of queen loss.

Call it convenient or good timing, but the book on the table right now is Atul Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto. It feels like the right companion as we get things off the ground in the coming weeks and months, translating training notes into checklists and routines around live colonies.

Ending with another book: Beesalu (Malayalam title), authored by indigenous communities of the Western Ghats, from Neelambur to be exact. It documents traditional honey collection practices and the communities around them, and one of the authors was present at The Habba on 21 December 2025 as part of The Nilgiris Earth Festival.

From here, the focus shifts to Mysuru: one hive to begin with, set up carefully and observed often. Those early days will shape how FarmSay works with bees, and the notes from that journey will continue to live here for anyone curious to follow along.